Posted by Sean Corrigan on Fri, Oct 06, 2023 @ 3:40 AM

How Landscape Architects Plant Trees in Cities

Landscape architects are experts in designing and creating beautiful, sustainable landscapes. One of the essential components of their work is planting trees in urban environments. Trees provide numerous benefits to the urban environment, including enhancing air quality, reducing stormwater runoff, and providing shade and habitat for wildlife. In this section, we will explore how landscape architects plant trees and the techniques they use to ensure their success.

Key Takeaways:

- Landscape architects play a crucial role in planting trees to create sustainable and healthy environments.

- Proper selection of tree species, planting techniques, and maintenance are essential for the long-term health of trees.

- Landscape architects navigate unique challenges when planting trees in urban environments.

- By following best practices in tree planting, we can contribute to a greener and healthier future.

The Importance of Tree Planting for Urban Landscapes

Tree planting is an essential component of creating sustainable and healthy environments, especially in urban areas. Landscape architects follow best practices to ensure the successful establishment and growth of trees, including sustainable tree planting and urban tree planting.

One of the critical tree planting best practices is selecting appropriate tree species. Landscape architects carefully choose the tree species that are well-suited to the local climate and site conditions. They prefer native tree species as they provide numerous benefits, such as supporting local wildlife and improving biodiversity.

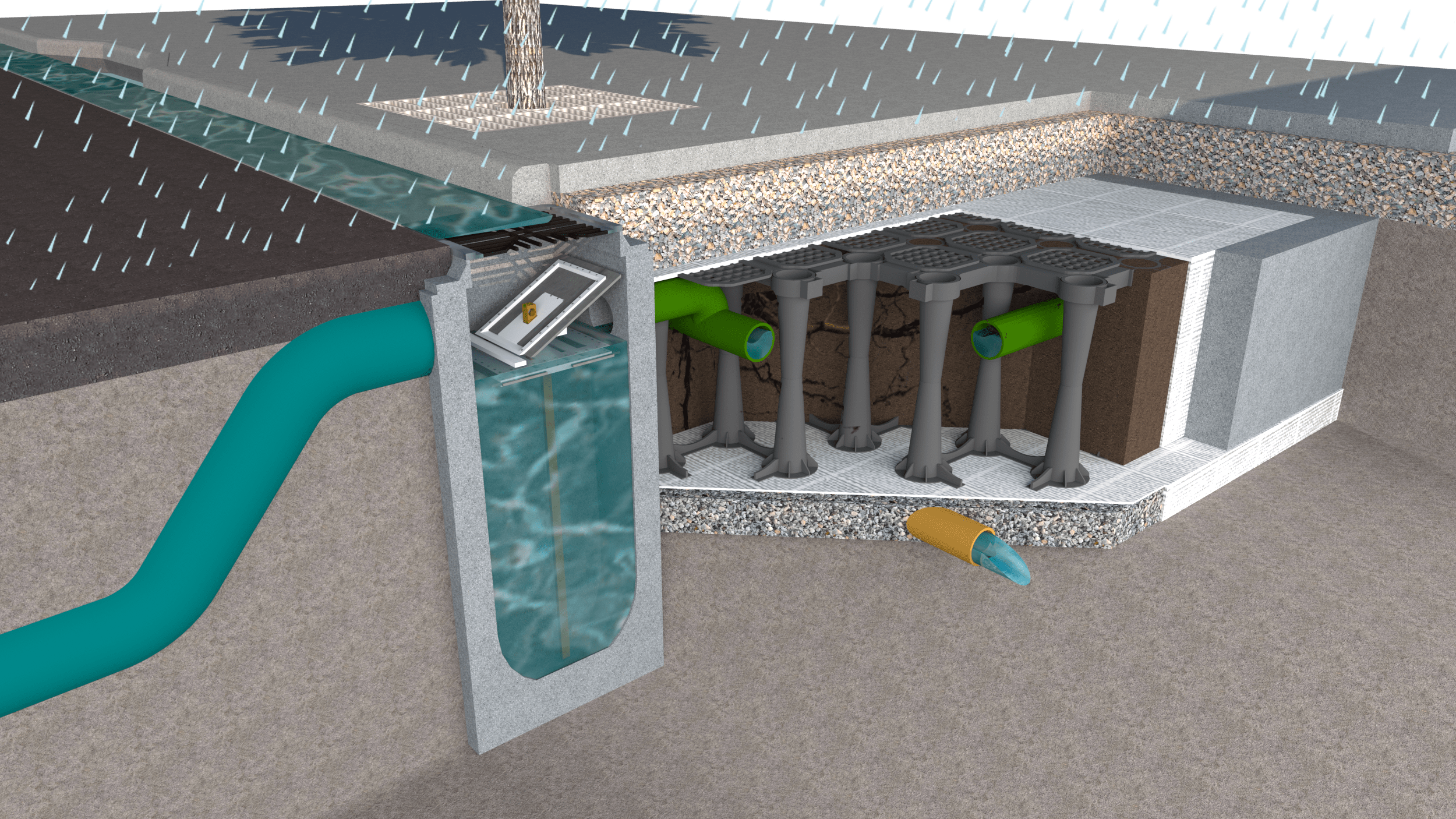

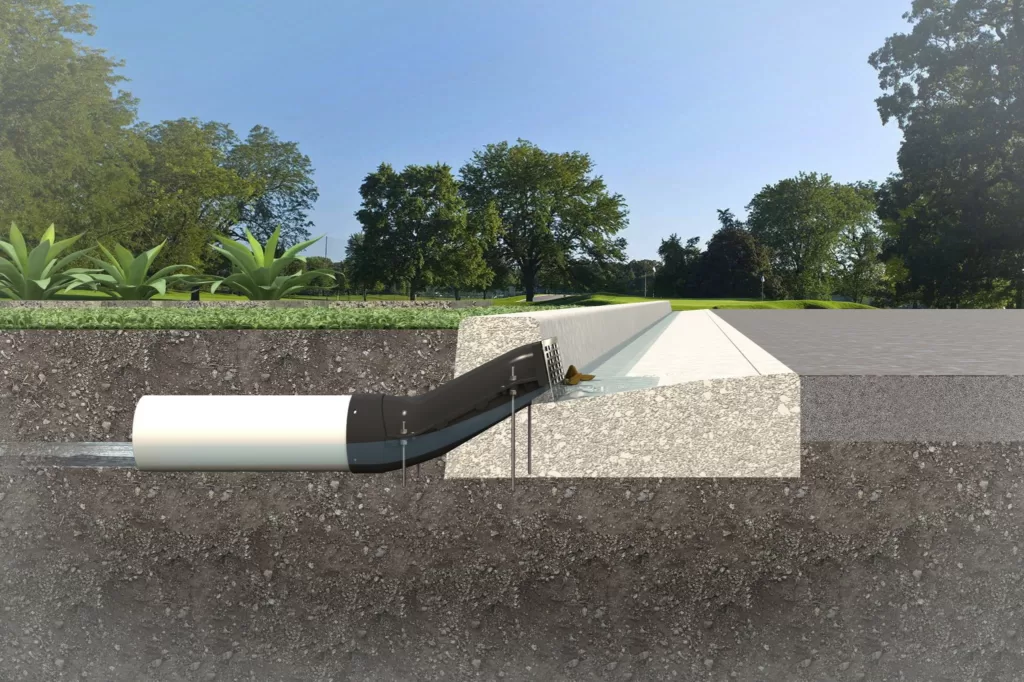

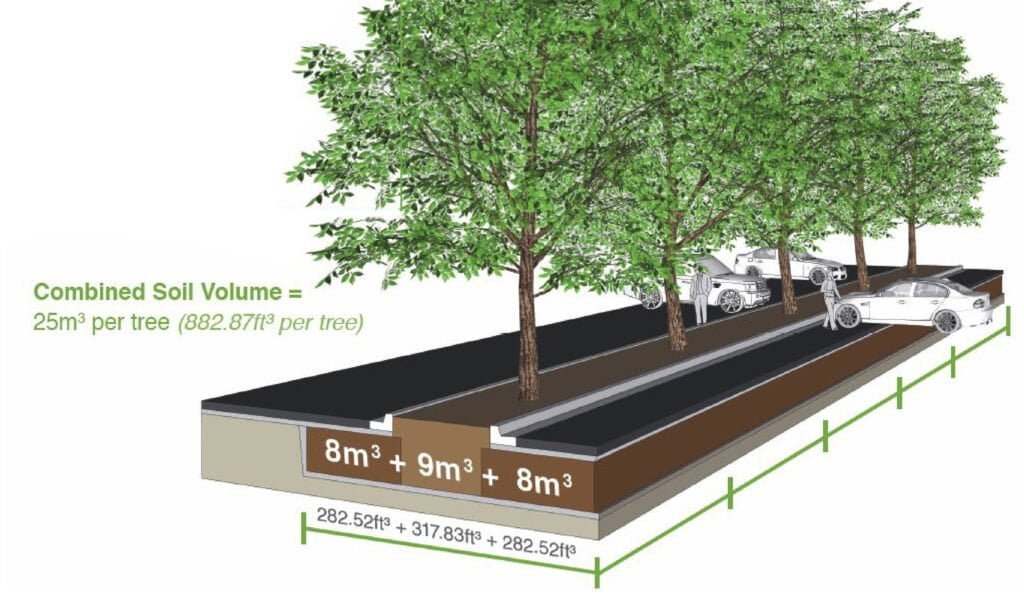

Soil and tree root preparation is crucial for sustainable tree planting. Landscape architects use innovative techniques like soil cells, such as Stratavault or soil vault systems, to ensure adequate space for root growth and improve soil quality. This is especially important in urban areas where soil compaction and pollution can be a significant challenge.

Tree roots are opportunistic, seeking out favorable growing conditions. Moisture trapped beneath impermeable pavements, oxygenated sand layers, moist conditions in service trenches, cracks in road pavements and curbs- these are some areas that tree roots will explore to satisfy the life needs of the tree which leads to pavement and infrastructure damage.

Landscape architects also employ various tree planting techniques to ensure proper tree planting. This includes preparing the hole properly, handling the root ball, and planting the tree at the correct depth. These techniques promote healthy root development and establish strong trees.

Proper maintenance is crucial for the long-term health of planted trees. Landscape architects monitor the trees for signs of stress, pests, or diseases. They provide necessary pruning, fertilization, and irrigation to ensure optimal growth and resilience. Moreover, they also consider factors like site conditions and tree spacing to optimize the tree’s health and longevity.

Overall, landscape architects prioritize sustainability in tree planting projects to ensure that the planted trees contribute to a resilient and environmentally friendly landscape. By following their best practices, we can contribute to a greener and healthier future.

Selecting Tree Species for your Landscape

When it comes to planting trees, landscape architects carefully consider which tree species to select. Native tree species are often preferred, as they are better adapted to the local climate and conditions and can provide numerous benefits. In fact, selecting the right species can make all the difference in the success of a tree planting project.

Native trees also support local wildlife and improve biodiversity. They are often hardier than non-native species, able to withstand harsh weather conditions and local pests and diseases. Additionally, native species are more likely to support the specific ecology of the area, including pollinators like bees and butterflies.

Related: Best Species for Reducing Air Pollution

However, it’s not just about selecting native species. Landscape architects also take into account factors such as tree growth rate, size, and appearance to ensure the right tree is selected for the right location. They also consider the soil conditions and water availability, as well as any potential hazards that may impact the growth of the tree.

By carefully selecting the appropriate tree species, landscape architects can create healthier and more resilient urban forests. Not only do these trees provide environmental benefits, but they also contribute to the beauty of our urban landscapes.

Tree Planting Techniques

Proper tree planting techniques are essential for successful tree growth and development. Landscape architects utilize various methods to ensure optimal tree health.

One crucial technique is proper hole preparation. The hole should be dug to the appropriate depth and width, allowing enough space for the roots to spread out. The root ball should be handled carefully to prevent damage. The edge of the root ball should be lightly hand brushed to bring all the fine roots out and larger structural roots at the edge of the root ball should be pruned if their roots are facing inward to avoid root swirl. We do this to ensure once the tree is planted in it’s new surroundings new growth is focused on growing outwards into new soil.

Correct planting depth is also important. The topmost root of the tree should sit slightly above the soil level to prevent it from suffocating. After planting, the soil should be carefully compacted to eliminate air pockets and provide support for the young tree.

Overall, landscape architects should follow specific tree planting methods that ensure the long-term success of the planted trees.

Soil Preparation and Soil Cells

Landscape architects understand the critical role of soil preparation in ensuring successful tree planting. They use innovative techniques like soil cells to improve soil quality and provide adequate space for root growth, promoting healthy trees.

Related: How much Soil do Street Trees Need?

Soil cells are a specially designed system that provides structural support for pavements and surfaces while simultaneously providing ample space for root growth and water drainage. Stratavault and soil vault systems are examples of these systems that feature an interlocking matrix design that creates ideal conditions for soil moisture and movement.

| Advantages of Soil Cells | Disadvantages of Soil Cells |

|---|---|

| * Improved soil structure and quality * Prolonged tree lifespan * Enhanced stormwater infiltration and drainage * Reduced soil compaction and increased porosity * Prevents root damage from construction or digging * Lower lifetime maintenance cost of surrounding infrastructure | * High initial installation cost |

By using soil vault systems such as those created by Citygreen, landscape architects can promote healthy tree growth and create sustainable landscapes that benefit both the environment and the community.

Tree Planting Best Practices

Related: Ultimate Guide on How to Plant Trees in Urban Areas

Planting a tree is more than just digging a hole and dropping in the sapling. It requires careful consideration and attention to detail to ensure the tree has the best chance of thriving for years to come. Here are some best practices for tree planting:

- Proper Mulching: Adding a layer of organic mulch around the base of the tree can help retain moisture and suppress weeds. However, make sure to keep the mulch away from the trunk to prevent rot.

- Adequate Watering: Newly planted trees require regular watering to establish their root system. Depending on the climate and soil conditions, this may mean watering daily or a few times per week.

- Regular Maintenance: Trees require ongoing care, such as pruning and fertilization, to maintain their health and shape. Regular inspection for pests and diseases is also critical to prevent issues from becoming more severe.

- Site Conditions: Consider the specific site conditions, such as sun exposure and soil type, when selecting and planting trees. This will help ensure the tree is well-suited to its environment and has the best chance of thriving.

- Tree Spacing: Proper tree spacing is crucial to avoid overcrowding and competition for resources. Landscape architects consider factors such as mature tree size, growth rate, and root system when determining appropriate spacing.

By following these best practices, you can help ensure the long-term health and success of your newly planted trees.

Maintaining Tree Health

Proper maintenance is essential for ensuring the long-term health and vitality of planted trees. Landscape architects follow specific best practices when it comes to tree planting, and these practices extend to tree maintenance as well.

One of the most critical aspects of tree maintenance is monitoring the trees for signs of stress, pests, or diseases. Early detection and treatment are essential to prevent further damage and maintain optimal tree health. Landscape architects also provide necessary pruning, fertilization, and irrigation to promote healthy growth and resilience.

When it comes to pruning, it’s important to follow industry best practices. Incorrect pruning techniques can lead to damage and even death of the tree. Landscape architects use specialized tools and techniques to remove dead or diseased branches, promote proper growth, and maintain the tree’s overall health.

Fertilization is another critical aspect of tree maintenance. Landscape architects apply appropriate fertilizer to provide essential nutrients to the tree’s roots, promoting vigorous growth and a healthy canopy. Proper watering is also crucial, with landscape architects recommending deep and infrequent watering to promote root growth and water efficiency.

In addition to these best practices, landscape architects also consider factors like site conditions and tree spacing when it comes to tree maintenance. They take steps to prevent damage caused by lawn equipment or other external factors and ensure that the tree has adequate space to grow without competing with nearby trees or infrastructure.

In summary, proper maintenance is essential for the long-term health and vitality of planted trees. Landscape architects follow specific best practices when it comes to pruning, fertilization, and watering, and monitor trees for signs of stress, pests, and disease. By following these practices, they ensure that planted trees thrive and contribute to the overall beauty and sustainability of our landscapes.

Ensuring Sustainability

Landscape architects understand the importance of planting trees with sustainability in mind. They consider factors such as water efficiency, carbon sequestration, and the overall ecological impact when designing a planting project.

By selecting appropriate tree species and employing proper planting techniques, landscape architects create healthy ecosystems that provide numerous benefits to the environment and local communities.

But sustainability doesn’t end with the planting phase. Proper maintenance, such as regular pruning and fertilization, helps promote long-term growth and ensures the trees continue to provide environmental benefits for years to come.

By prioritizing sustainable tree planting, landscape architects contribute to a healthier and more resilient future for our planet.

Urban Tree Planting Challenges

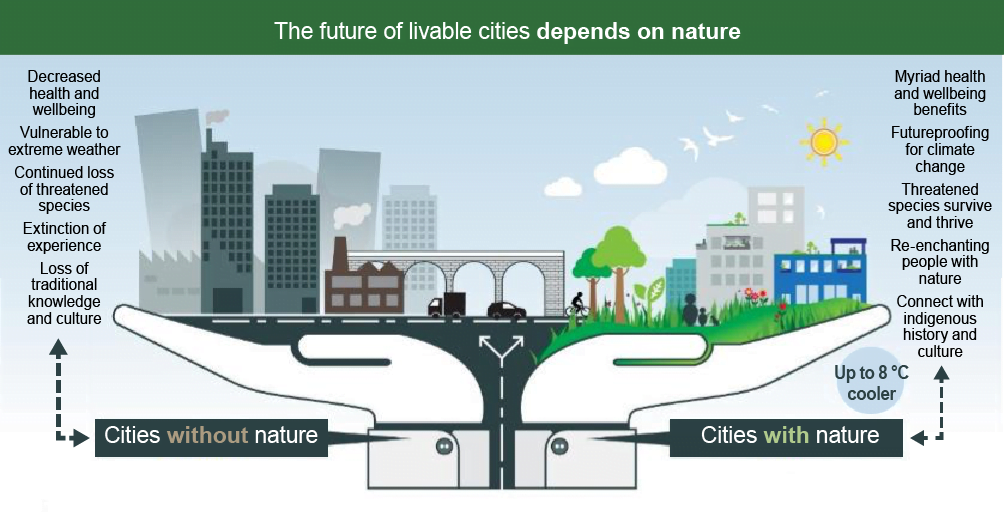

Planting trees in urban areas can be challenging due to various factors. Landscape architects face obstacles such as limited space, soil compaction, and pollution that can affect the growth and health of trees. Despite these challenges, there are innovative techniques that can help overcome these issues.

One of the main challenges of urban tree planting is limited space. In urban environments, space is at a premium, and finding adequate space to plant trees can be a challenge. Landscape architects use techniques such as vertical planting, tree pits, and raised planter beds to create more space for tree growth.

Soil compaction is another issue that landscape architects face when planting trees in urban areas. Compacted soil can limit root growth and the ability of trees to absorb water and nutrients. Landscape architects use techniques such as soil aeration and the installation of soil cells, like Stratavault or soil vault systems, to provide more space for root growth and improve soil quality to ensure trees have the best possible conditions to thrive in urban environments.

Pollution is also a major concern when planting trees in urban environments. Air pollution can damage leaves and limit growth, while soil pollution can affect the health of tree roots. Landscape architects choose tree species that are resistant to pollution and use air and soil filtration systems to improve air and water quality.

Despite these challenges, landscape architects are committed to creating green urban environments through sustainable tree planting practices. By utilizing innovative techniques and selecting the right tree species, they can build thriving urban forests that make our cities healthier, more resilient, and more beautiful.

Conclusion

In conclusion, landscape architects are an essential part of creating sustainable and healthy environments by planting trees. By following their best practices and techniques, they ensure the successful establishment and growth of urban green spaces. From selecting appropriate tree species to employing proper planting techniques, landscape architects play a critical role in establishing thriving urban forests. Their expertise in maintaining tree health and ensuring sustainability contributes to a greener and healthier future for us all. Through their dedication and hard work, landscape architects demonstrate how planting trees can positively impact our communities and the environment. So, if you want to learn how landscape architects plant trees and help create a greener future, keep exploring and discovering!

FAQ

How do landscape architects plant trees?

Landscape architects plant trees using various techniques, such as proper hole preparation, handling root balls, and ensuring the correct planting depth. These techniques promote healthy root development and establish strong trees.

Why is tree planting important?

Tree planting is important because it contributes to creating sustainable and healthy environments. Landscape architects follow best practices to ensure successful tree establishment and growth in urban areas, considering factors such as soil conditions, water availability, and selecting appropriate tree species.

How do landscape architects select tree species for planting?

Landscape architects carefully choose tree species that are well-suited to the local climate and conditions. Native tree species are often preferred as they are adapted to the environment and provide numerous benefits, such as supporting local wildlife and improving biodiversity.

What techniques do landscape architects use for tree planting?

Landscape architects employ various techniques for tree planting, including proper hole preparation, root ball handling, and ensuring the correct planting depth. These techniques help promote healthy root development and establish strong trees.

What is soil preparation and how does it relate to tree planting?

Soil preparation is an essential step in successful tree planting. Landscape architects may use innovative techniques like soil cells, such as Stratavault or soil vault systems, to provide adequate space for root growth and improved soil quality.

What are some tree planting best practices?

Landscape architects follow specific best practices when planting trees, including proper mulching, adequate watering, and regular maintenance. They also consider site conditions and tree spacing to optimize tree health and longevity.

How do landscape architects maintain tree health?

Landscape architects monitor planted trees for signs of stress, pests, or diseases and provide necessary pruning, fertilization, and irrigation to ensure optimal growth and resilience.

How does tree planting contribute to sustainability?

Landscape architects prioritize sustainability in tree planting projects, considering factors like water efficiency, carbon sequestration, and overall ecological impact. This ensures that planted trees contribute to a resilient and environmentally friendly landscape.

What are the challenges of urban tree planting?

Urban environments pose unique challenges for tree planting, such as limited space, soil compaction, and pollution. Landscape architects employ innovative techniques to overcome these challenges and create thriving urban forests.

How do landscape architects contribute to creating sustainable landscapes?

Landscape architects play a critical role in planting trees and creating sustainable landscapes. Their expertise in selecting tree species, employing proper planting techniques, and ensuring long-term tree health results in beautiful and thriving urban green spaces.