Posted by Sophie Nichols on Wed, Sep 14, 2022 @ 5:39 AM

How to Manage Stormwater Sustainably

An article published online by editor and writer Melissa Denchak highlighted some shocking stormwater statistics coming out of America. Denchak stated that ‘an estimated 10 trillion gallons of untreated stormwater runoff, containing everything from raw sewage to trash to toxins, enters U.S waterways from city sewer systems every year, polluting the environment and drinking supplies… [with] runoff causes significant flooding as well.’ (Denchak 2022).

Table of Contents

Denchak described the ‘U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that upgrading the stormwater and other public water systems will require at least $150 billion in investment over the next two decades.

This problem is not unique to the U.S, it is a problem all over the globe. The question is, how do we address the issues caused by stormwater runoff?

In this article, Citygreen will argue that green infrastructure offers a cost-effective solution to handling flooding and stormwater pollution.

To start, let’s break down the basics.

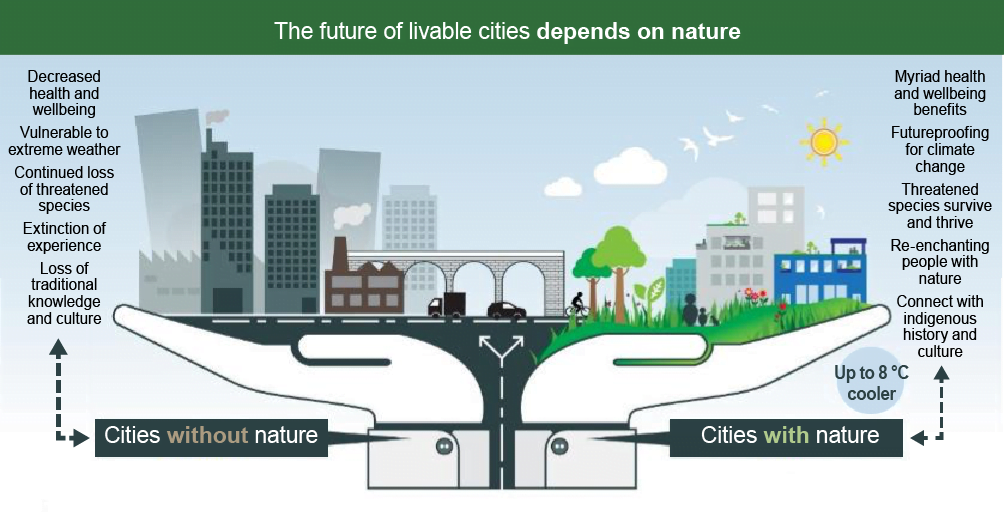

Why is Green Infrastructure Important for Managing Stormwater?

Green infrastructure sets out to replicate the circular economy of the natural environment. Attempting to mirror the efficient and self-renewing processes found in nature.

In urban settings, green infrastructure encompasses a variety of water management practices, such as treepits, planted verges, bioretention pits, swales and other measures that capture, filter, and reuse stormwater. Essentially, green infrastructure replicates natural hydrological processes using soil and plants to slow down, recycle and clean stormwater runoff.

What is Stormwater Runoff?

Stormwater runoff is the product of a rain event causing water to flow across the land into sewers and waterways. With the expansion of our bustling cities and the widening sprawl of our urban areas, there are more impermeable surfaces than ever, increasing the intensity of stormwater runoff.

According to Denchak, ‘the average city block can generate more than five times as much runoff as a forested area of equal size’ (Denchak 2022).

What is an Example of a Successful Green Infrastructure Project?

Denchak proposed that New York’s Staten Island Bluebelt was the ‘first and largest green infrastructure project in the U.S.’ A rapid increase in population size saw the Island struggling to deal with sanitary waste and stormwater runoff.

The Bluebelt project ‘helped solve these issues by preserving streams, wetland areas, and other drainage corridors (Bluebelts) that use natural mechanisms to capture, store, and filter stormwater’ (Denchak 2022). Nowadays, the Bluebelt comprises more than 14,000 acres and can temporarily hold and filter as much as 350,000 gallons of rainfall.

How does Citygreen Implement and Manage Stormwater Projects?

Over the past three decades, Citygreen has made significant investments in stormwater infrastructure projects. We learnt early on that mimicking natural systems to manage rainfall, is the most cost-effectively way to deal with stormwater runoff.

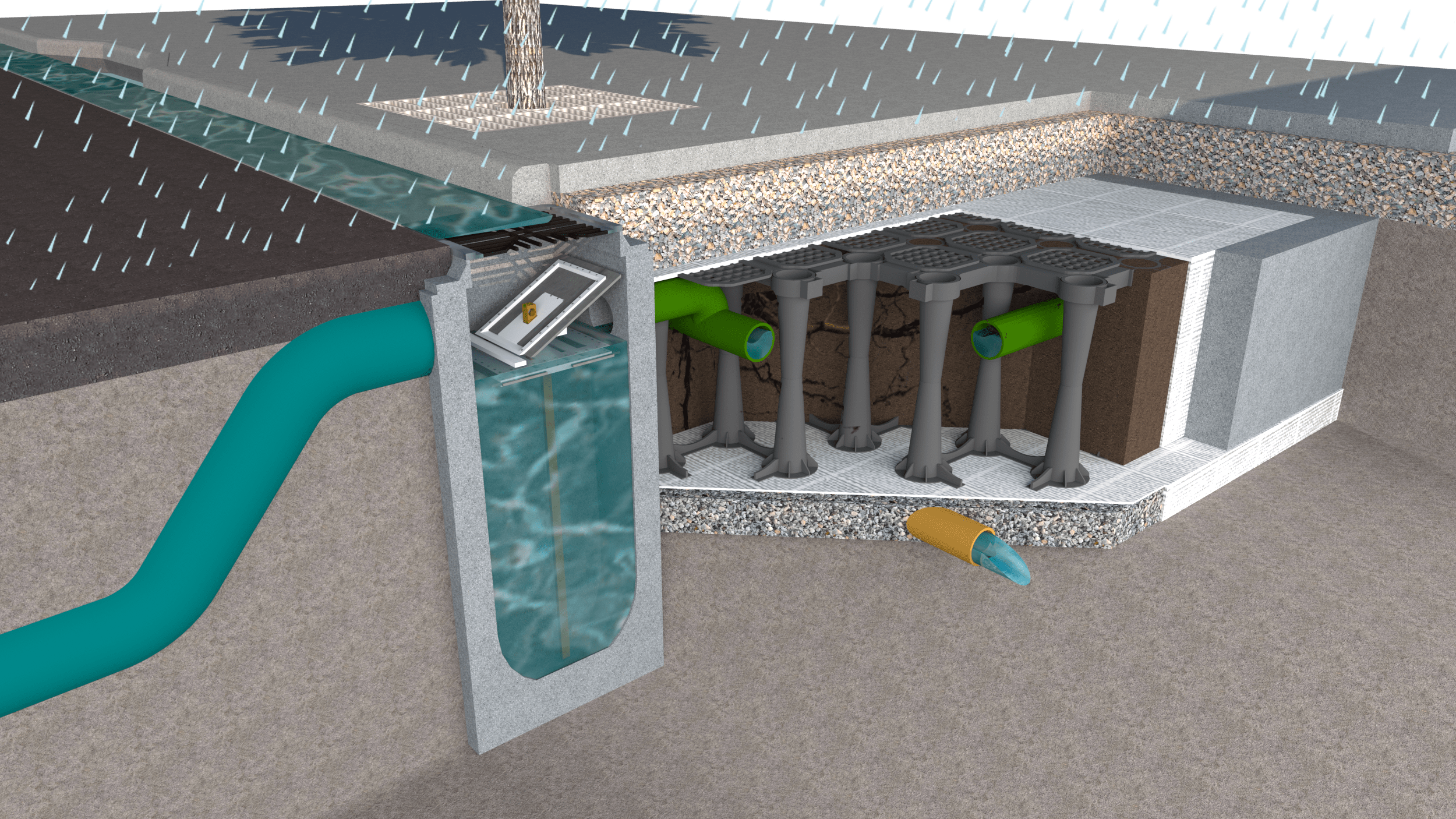

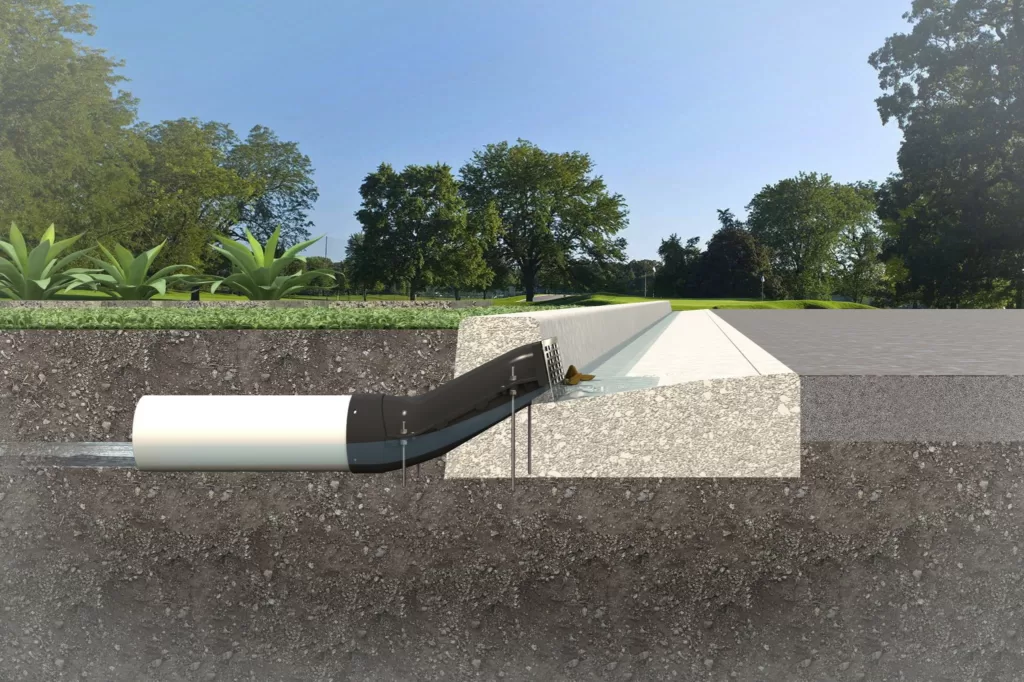

An example of a green infrastructure design that Citygreen has developed is the Strataflow™ system. Instead of a traditional bioretention basin, Citygreen’s Strataflow™ uses an underground structural soil vault system, which delivers a high standard of stormwater treatment with a completely natural look. To any passer-by, what you see is a healthy, flourishing tree surrounded by a grassy verge, but beneath the ground is an advanced WSUD(water sensitive urban design).

This design starts with a traditional drain or catch basin or the Strataflow Kerb Inlet; this device sits in the road kerb alignment, retaining the inherent structure of the concrete kerb. The inlet has a grate (acting as a screen) to stop larger-sized pollutants from entering the system, which inhibits healthy tree growth.

The inlet lets water from the road carriageway flow through the front grate of the drain at a capacity of up to 18 litres/ 5 gallons per second. This allows the inlet to minimise pollutants entering waterways and reduce flood risks by controlling the stormwater flow entering our city’s underground drains.

When the water flows through the street, it enters through the inlet and flows underground. From there, the stormwater reaches the advanced structural soil cell system, where the stormwater is stored, filtered and distributed effectively for the benefit of urban trees and proper stormwater management.

The inlet ensures the water drains down at the correct optimal depth beneath the pavement height. From there, the stormwater reaches the structural soil cell system and the tree’s root system, where the stormwater is stored, cleaned and distributed effectively to increase urban tree growth and proper stormwater management principles.

Essentially, Strataflow™ utilises readily available stormwater rather than potable water to irrigate street trees, which improves the vitality of trees and reduces the impact of stormwater and stormwater contaminants on the local environment, all while maintaining a high natural presentation.

Stormwater Management Case Study

Pemberton is a small mountain town located 20 minutes North of world-renowned ski resort Whistler in Beautiful British Columbia, Canada.

In 2019 the town of Pemberton was awarded a government grant to upgrade ageing infrastructure and give their tourist town a facelift. Pemberton had some issues with flooding which they were keen to fix and at the same time wanted to create an inviting and enjoyable experience for the visitors and residents of the town.

One of the solutions was the Stratavault system, this system was placed underneath all sidewalks for two reasons. The first was to collect the mass of snow run off and rainfall that would typically flood the town, slow this water down and clean it with the soil held in the Stratavault system then push excess water into a nearby pond where it could be used for irrigation purposes throughout the town. The second was to hold enough soil so the trees that were planted in urban environments could have access to nutrient-rich soil for many years to come.

Book a Citygreen Consultant

Looking for a cost-effective and sustainable stormwater solution? Contact our friendly Citygreen Team today.